A blueprint for integrated health and wellbeing

Conor McClean of Public Health Scotland explains the nation’s tiered approach to physical activity interventions

Physical inactivity remains one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time. In Scotland, 63% of adults meet the Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO) guidelines for moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA), yet only 29% achieve the combined recommendation of MVPA and muscle-strengthening activity. Almost half of adults live with one or more long-term conditions, and 37% report that these conditions limit their daily activities. The Scottish Government has set an ambitious target: reduce physical inactivity by 15% by 2030, in line with the WHO Global Action Plan on Physical Activity.

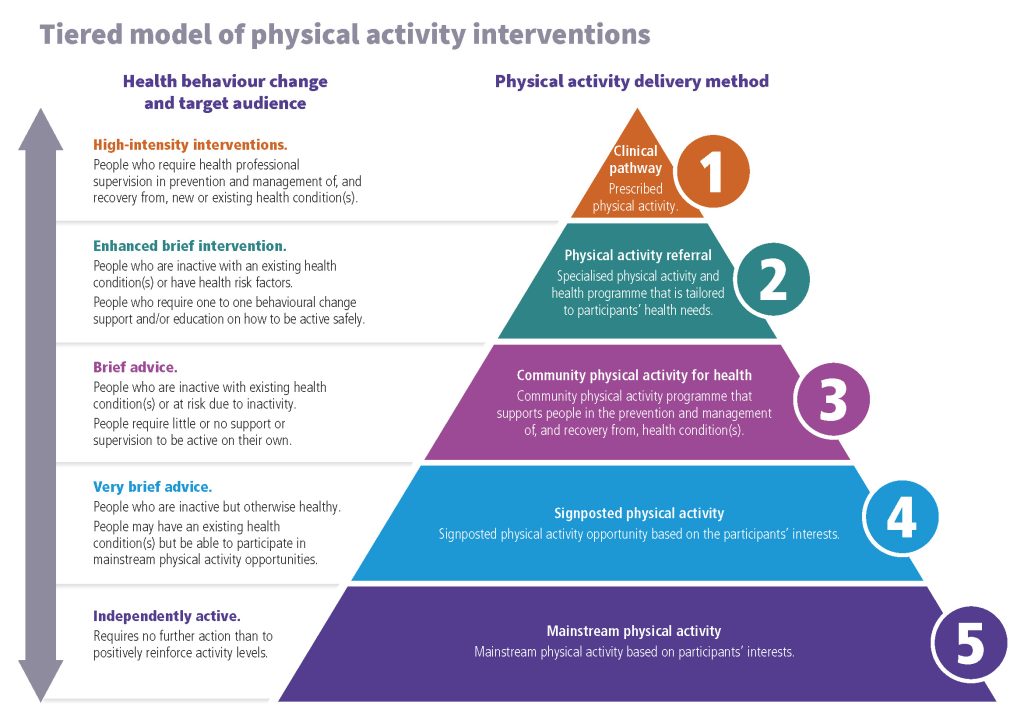

Against this backdrop, Scotland has revisited its approach to physical activity interventions, creating a tiered model that integrates healthcare, community and mainstream activity opportunities. This article explores why the model was refreshed, who it aims to support, the challenges faced, early impacts, lessons for other home nations, and what’s next.

Why has the tiered approach been revisited?

The tiered approach was originally developed within our Physical Activity Referral Standards to provide clarity and consistency across Scotland’s health and physical activity systems.

Public Health Scotland’s systems-based framework highlighted the importance of embedding physical activity into healthcare pathways. The National Physical Activity Pathway (NPAP) and Physical Activity Referral Standards (PARS) were introduced to ensure that healthcare professionals could confidently assess, advise and refer patients to appropriate interventions. Revisiting the tiered approach allowed Scotland to:

- align interventions with national and international best practice

- create clear definitions for each tier, from clinical pathways to mainstream activity

- support triage and progression, ensuring people receive the right level of support at the right time.

The refreshed model emphasises behaviour change as a core component, recognising that knowledge alone does not lead to sustained activity. It also addresses inequalities by ensuring opportunities exist for those facing the greatest barriers.

Who is this for?

The tiered approach is designed for everyone – from individuals with complex clinical needs to those ready to engage in mainstream physical activity. Its five tiers are:

- Clinical pathway: For people requiring supervised, clinically prescribed programmes.

- Physical activity referral: For those with health conditions or risk factors needing tailored support.

- Community physical activity for health: For inactive individuals motivated to take action with minimal supervision.

- Signposted physical activity: For those who can engage in mainstream opportunities with little support.

- Mainstream physical activity: For people already active, requiring only positive reinforcement.

The overarching goal is to help people become independently active by addressing barriers – whether physical, psychological, social or environmental. For the NHS, this means reducing the burden of disease linked to inactivity and improving population health outcomes.

We hope that the tiered approach would achieve this aim by helping:

- commissioners to commission, plan and review the delivery of appropriately designed interventions

- referrers know what level of intervention to refer or signpost people to

- service providers to map current provisions, plan services, develop physical activity interventions based on local need and to inform triage and exit routes from their interventions.

What challenges have you discovered and how did you overcome them?

One of the key challenges was ensuring alignment across different parts of the system –clinical services, referral schemes and community programmes. With so many organisations involved, it was sometimes difficult to create a shared understanding of pathways and responsibilities, which could lead to variation in how people accessed support.

Another area for development was building confidence and capability around health behaviour change. This is a specialist skill that underpins successful interventions, and while many practitioners were already doing great work, there was an opportunity to strengthen consistency and embed best practice across all tiers.

To address these challenges:

- Scotland introduced CIMSPA-endorsed professional standards and CPD pathways within the tiered model knowledge and skills framework, ensuring practitioners have the skills to deliver interventions at each tier

- clear tier definitions and triage guidance were developed, helping referrers and providers map local provision and plan exit strategies

- partnerships between healthcare, local authorities and physical activity providers were strengthened, creating a more integrated system.

What impact are you seeing so far?

Early feedback suggests the tiered approach is improving clarity and confidence among professionals. Referrers now understand which level of intervention best suits an individual’s needs, while providers can design services that align with national standards.

Local mapping exercises have revealed gaps in provision, enabling targeted investment. Exit strategies – such as moving participants from Tier 2 referral schemes to Tier 5 mainstream activity – are becoming more common, supporting long-term behaviour change.

Although comprehensive evaluation is ongoing, anecdotal evidence points to increased uptake of referral schemes and better engagement in community programmes. Professionals report that the structured approach has enhanced collaboration and reduced duplication.

What can other home nations take from Scotland’s work?

Scotland’s experience offers valuable lessons:

- Adopt a systems-based approach that connects healthcare, community, and mainstream activity.

- Use a tiered model to provide clarity for referrers and service providers.

- Embed behaviour change training across all tiers, recognising its role in sustaining activity.

- Align interventions with national guidelines and professional standards, ensuring quality and consistency.

By implementing these principles, other home nations can create integrated pathways that support people to be active for life.

What’s next? Plans for future review?

The tiered approach is not static. Public Health Scotland will continue to monitor and evaluate its impact through NPAP and PARS. Future reviews are likely to coincide with progress toward the 2030 inactivity reduction target.

Emerging priorities include:

- Review and redevelop our NHS Physical Activity Pathway (including PARS and the tiered model)

- Strengthening partnerships across health, social care, and physical activity sectors.

- Addressing inequalities by tailoring interventions for underserved communities.

Scotland remains committed to continuous improvement, ensuring its approach evolves with evidence and practice.

Conclusion

Scotland’s tiered approach to physical activity interventions represents a significant step toward integrated, person-centred care. By combining clinical expertise, community support and mainstream opportunities within a clear framework, Scotland is creating a culture where physical activity is the norm – not the exception.

As other home nations seek to tackle inactivity, Scotland’s model offers a practical blueprint for success. The message is clear: collaboration, consistency and commitment to behaviour change are key to building a healthier, more active population.